The Black Butterfly and Green Space in Baltimore

Understanding Baltimore’s Struggles with Racism, Inequality, and Green Space

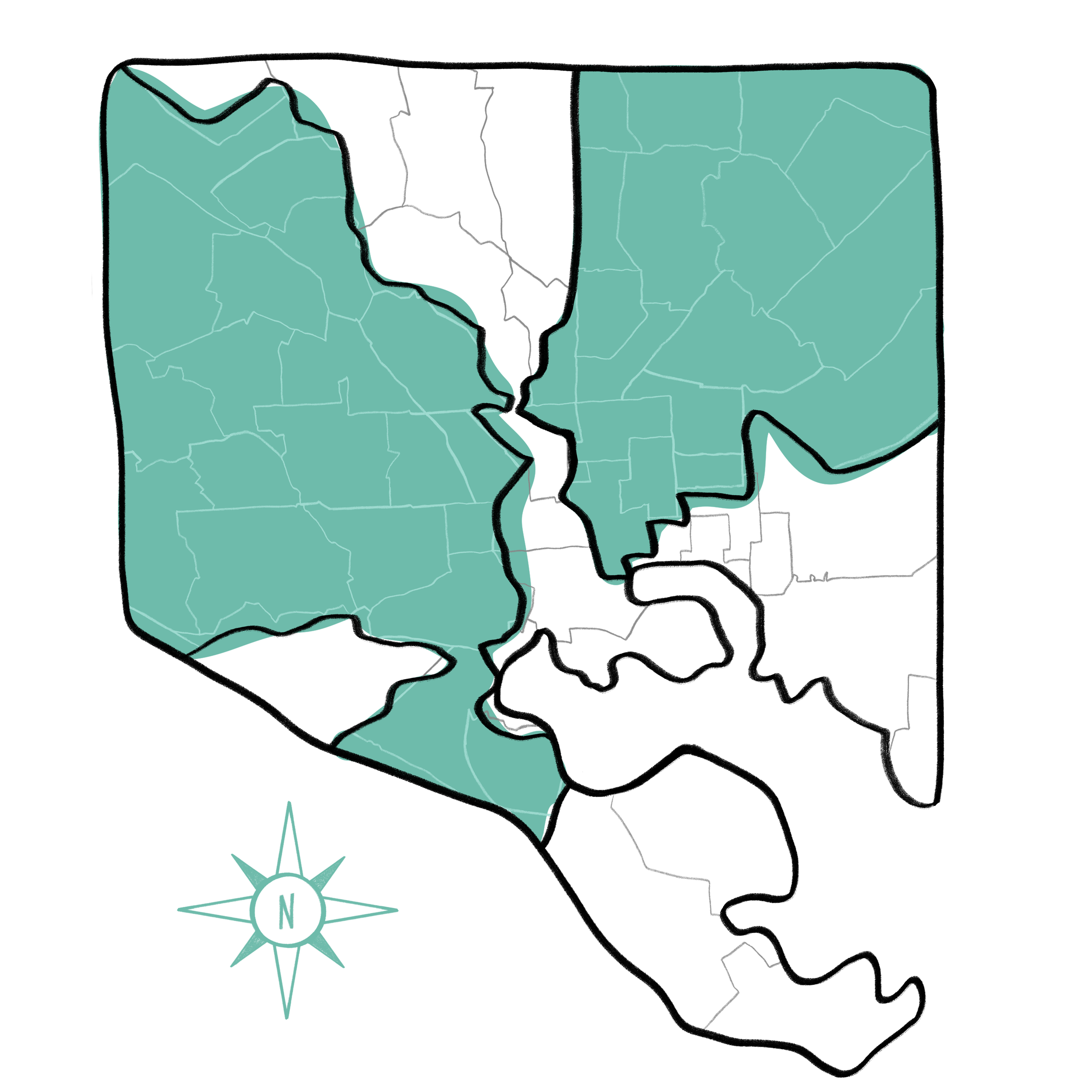

Darius White, Director of Park Projects at Park & People, explains Baltimore’s Black Butterfly.

One must look to the past in order to understand Baltimore’s current struggles with racism, inequality, and lack of green space. Dr. Lawrence T. Brown, director of the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, provides an especially compelling analysis of Baltimore’s racial inequality through his research on the “Black Butterfly”. In his book The Black Butterfly: The Harmful Politics of Race and Space in America, Brown writes:

After losing the war against the 'Negro Invasion' in the mid-1970s, Baltimore City's government shifted strategies and turned to a spatial war on Black neighborhoods, giving rise to a hypersegregated city. An examination of a racial dot map of Baltimore City reveals the city's spatial and racial geography in the form of a White L and a Black Butterfly.

What is Baltimore’s Black Butterfly?

Brown highlights the stark divide between the predominantly White, resource-rich ‘L’ of Baltimore and the underinvested, majority-Black neighborhoods forming the wings of the butterfly.

Brown emphasizes that the Black Butterfly was not an accident or unplanned. The segregation was carefully crafted through decades of discriminatory policies and practices. In 1911, Baltimore passed the nation’s first housing segregation ordinance targeted at preventing Black residents from living in predominantly White neighborhoods. Baltimore’s mayor addressed the plan in unabashed terms:

Blacks should be quarantined in isolated slums in order to reduce the incidence of civil disturbance, to prevent the spread of communicable disease into the nearby White neighborhoods, and to protect property values among the White majority

When the Supreme Court struck down a similar Kentucky law in 1917, city officials found other ways to enforce segregation, including citing code violations to anyone who sold property in predominantly White neighborhoods to Black people.

Baltimore Redlining and the Economic Consequences of Segregation

Following the Great Depression, the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) targeted majority-Black communities with redlining. The HOLC created maps assessing risk investment for different neighborhoods. They considered majority-Black neighborhoods to be the riskiest investment, marking them with red. This cut off access to home loans and investment for much of Baltimore’s Black population. Despite comprising 20% of the population, these policies confined Black households to just 2% of Baltimore’s land.

This structural segregation has driven stark economic disparities. A Brookings study revealed that homes in majority-Black neighborhoods sell for $48,000 less on average than similar homes in majority-White areas. These systemic inequities have left Black communities deprived of the investment and resources that they need to thrive.

Why The Butterfly Matters

Health Disparities in Redlined Neighborhoods

The consequences of this segregation are profound. Historically redlined neighborhoods, primarily located within the Black Butterfly, face a range of health disparities. Research from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC) shows significant associations between redlining and health issues like asthma, diabetes, and heart disease. These communities also experience higher rates of mental health challenges and reduced life expectancy compared to their counterparts in the White L.

Lack of Green Space and Its Impact

The disparities don’t end there. The systematic disinvestment in Black neighborhoods has deprived residents of basic amenities, including grocery stores, banks, and—critically—green spaces. Green spaces are critical resources that improve public health, foster community connection, and provide a safe space for children to play. Studies have shown that access to green space can reduce stress, improve physical health, and even lower crime rates. Yet parks and playgrounds are disproportionately concentrated in the wealthier, predominantly White areas of Baltimore. Meanwhile, Black neighborhoods often lack access to quality outdoor spaces. Such disparities exacerbate physical and mental health challenges, creating cycles of inequality that persist across generations.

Greening the Black Butterfly

Reversing Historical Injustices Through Green Space

Dr. Brown emphasizes the need for racial and spatial equity to restore underdeveloped Black neighborhoods. He writes:

Over the past 110 years, government-enforced racial segregation has constituted the platform from which structural weapons of environmental and economic destruction have been launched against Black neighborhoods.

Parks & People aims to combat these historical injustices by creating equitable green spaces that empower Baltimore’s Black Butterfly neighborhoods. For 40 years, we’ve focused on developing green spaces in Black Butterfly neighborhoods—areas where the median household income is less than $50,000 and over 40% of children live below the poverty line.

Transformative Urban Green Space Projects

One example of this work is Frances Ellen Harper Park, which serves more than 3,000 residents within a quarter-mile radius. Parks & People collaborated with neighborhood organizations to convert abandoned lots into a public green space. The park includes walking paths, landscaping, and recreational spaces, creating a hub for community engagement and well-being. Other projects range from pocket parks in Upton to Darley Park in East Baltimore Midway. Parks & People is dedicated to reversing racism’s corrosive effects on Baltimore’s well-being.

Join Us

Parks and People invites you to be part of this transformative mission. Whether through volunteering, donating, or spreading awareness, you can help us create a greener, more equitable Baltimore. Over the last 10 years alone, Parks and People has spearheaded more than 50 initiatives bringing green space to Baltimore’s Black Butterfly. Together, we can ensure that every neighborhood—regardless of its history—has access to the benefits of green space.